The origins of the Cu Chi tunnels date back to the late 1940s, when the Viet Minh, the nationalist movement that fought for Vietnam’s independence from French colonial rule, began digging tunnels to hide from the French army. The tunnels were dug by hand, using simple tools like hoes and baskets, and were only a few meters deep. The tunnels were mainly used for communication and supply routes, as well as hiding places during raids or bombings.

The tunnel network expanded significantly during the Vietnam War, which lasted from 1955 to 1975. The Viet Cong, who supported the communist government of North Vietnam, used the tunnels as their base of operations for guerrilla warfare against the American and South Vietnamese forces. The Cu Chi district, located about 60 kilometers northwest of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), was a strategic area for the Viet Cong, as it was close to the Cambodian border and the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a supply route that ran through Laos and Cambodia.

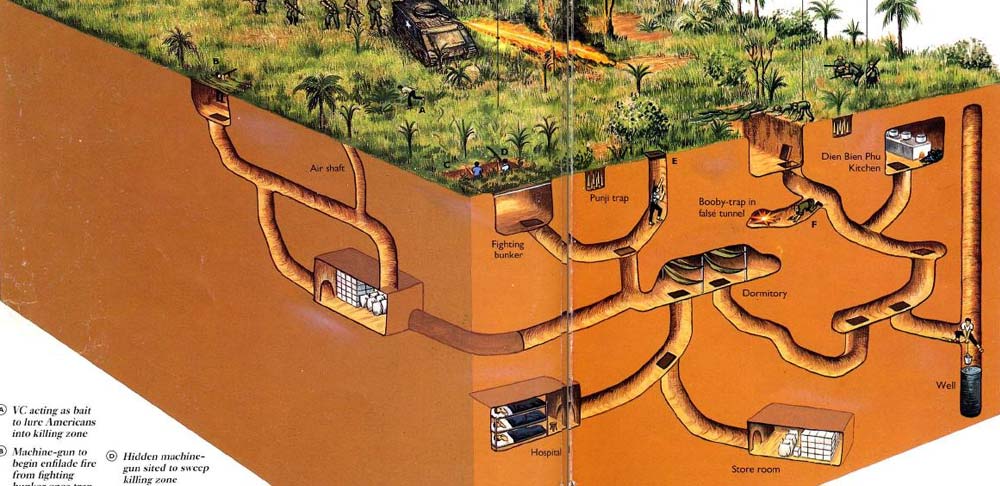

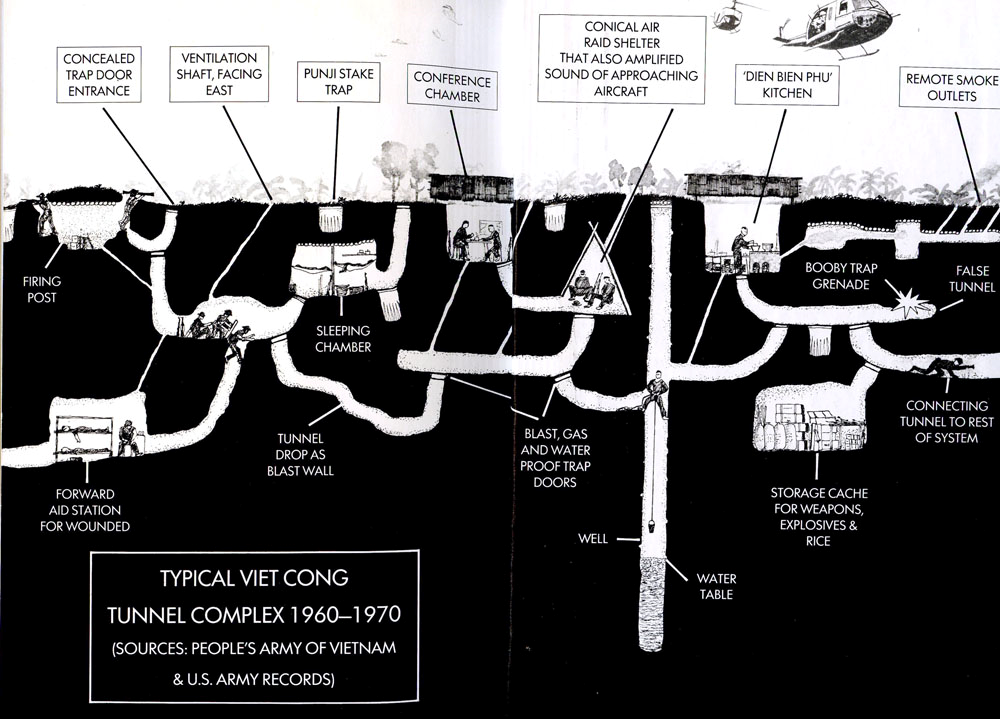

The Cu Chi tunnels covered an area of about 250 kilometers, and consisted of several levels and branches. Some tunnels were as deep as 10 meters, and could withstand bombs and artillery fire. The tunnels had various functions, such as living quarters, kitchens, hospitals, weapon factories, command centers, and bomb shelters. The tunnels also had traps, vents, and camouflaged entrances to prevent detection and infiltration by the enemy.

The Cu Chi tunnels played a vital role in several military campaigns during the Vietnam War. One of the most notable was the Tet Offensive in 1968, when the Viet Cong launched a surprise attack on more than 100 cities and towns in South Vietnam, including Saigon. The Viet Cong used the tunnels to move troops and weapons, launch ambushes, and then retreat underground. The Tet Offensive was a turning point in the war, as it shocked the American public and undermined their confidence in the war effort.

Life in the Cu Chi tunnels was harsh and dangerous for the Viet Cong soldiers and their supporters. They faced many challenges, such as lack of air, food, water, and sanitation. They also had to deal with insects, snakes, rats, and diseases. Malaria was a common cause of death among the tunnel dwellers. The Viet Cong had to follow strict rules of discipline and security, such as not smoking or cooking during the day to avoid smoke detection, or not talking loudly or making noises that could reveal their presence.

The American and South Vietnamese forces tried various methods to destroy or capture the Cu Chi tunnels. They used bombs, napalm, defoliants, dogs, probes, and gas to locate and attack the tunnels. They also trained special soldiers known as “tunnel rats” to enter the tunnels with flashlights and pistols and clear them of enemy troops. However, these methods were often ineffective or costly, as the Viet Cong were able to repair or rebuild the tunnels quickly or set up booby traps to kill or injure their pursuers.

The Cu Chi tunnels are now a memorial park and a popular tourist destination. Visitors can explore some parts of the tunnel system that have been widened and reinforced for safety. They can also see displays of weapons, traps, vehicles, and other artifacts from the war. Some visitors can even try shooting guns or tasting food that was eaten by the tunnel dwellers at nearby shooting ranges or restaurants.

The Cu Chi tunnels are a remarkable example of human ingenuity, resilience, and courage in the face of adversity. They are also a reminder of the horrors and tragedies of war that affected millions of lives on both sides. By visiting the Cu Chi tunnels, you can gain a deeper understanding of Vietnam’s history and culture.